It is easy to make an emotional case for Western assistance to the Ukrainian government in its confrontation with Russia. In principle, the people of Ukraine should have the liberty to determine their own foreign policy orientation and the international community should support their freedom to make this choice. Such a stance is morally unimpeachable. It is also a perilous basis for policymaking. Pursuing ideals in isolation from assessments of what is achievable and without reference to the broader international context risks unleashing a horror of unintended consequences. This being so, foreign policy makers must restrict themselves to the art of the possible and base their decisions on cold-hearted assessments of long-term security interests.

Based on the prioritization of such strategic goals, what should be the West’s Ukraine policy? There are those who believe that, on this occasion, realist and liberal goals coincide, and that security imperatives dictate that the West must act forcefully to end Russia’s intervention in its neighbor’s affairs. The argument here is that Vladimir Putin’s Russia is an aggressive, expansionist state whose actions, in the words of Chancellor Merkel of Germany, call “the whole of the European peaceful order into question.” What is at stake, therefore, is not just the status of one country but the fate of the entire postwar international system. This is because it is assumed that conceding to Russian demands in Ukraine will inevitably encourage it to advance elsewhere. Given the specter of Russian tanks rolling into the Baltic States, it is no surprise that many have come to favor supplying Kiev with “lethal defensive weapons.”

This makes for a compelling narrative, not least because it draws upon historical memories of appeasement and Nazi expansionism. In reality, however, the argument is without foundation. Economically weak and demographically in decline, Russia represents no serious threat to the international status quo. Indeed, holding a privileged position that it no longer merits, Russia has absolutely no incentive to challenge the postwar order. Moscow’s actions in Ukraine are therefore best interpreted, not as self-assured expansionism, but rather as the panicky response of an insecure state to a perceived threat to its fundamental national interests.

Even if Russia’s actions are driven by weakness and not strength, this does not necessarily mean that Western interests would not be best served by taking a forceful stance. What alters this calculation, however, is an assessment of the broader geopolitical implications of this policy. Regarded at a global level, the punishing sanctions regime and exclusion of Russia from Western groupings comes to look like a strategic mistake. This is because it is has had the effect of forcing Moscow to overcome its hesitations and commit fully to close relations with Beijing. Should this relationship evolve into a full-blown Chinese-Russian axis, it will be a development of historic proportions since, while Russia on its own does not seek to challenge the established international order, China certainly does. What is more, despite Russia’s diminished status, it is able to contribute significantly to Chinese international power. Closer bilateral relations can therefore be anticipated to encourage Beijing’s attempts to assert regional hegemony. In this way, by taking an uncompromising stance against its 20th century adversary in Europe, the United States may be inadvertently assisting its 21st century rival in Asia.

Russia as Status Quo Power

It may seem perverse to claim that a country that has recently annexed part of a neighboring state, and is currently engaged in backing a separatist insurgency, is a status quo power. Nonetheless, this is the case.

On a global level, Moscow strives to uphold the current international order since it flatters Russian power and constrains that of those mightier than itself. Above all, the current system gives Russia permanent membership of the United Nations Security Council, providing it with cherished equal status to the United States and China. The UN’s core principle of national sovereignty is also generally favored by Moscow because it can be used to place diplomatic obstacles in the path of U.S. foreign policy. An example of this is Russia’s appeal to national sovereignty and its use of veto power to protect Syria’s Assad regime from the threat of Western airstrikes. Evidently Moscow has shown no such respect for the concept of non-interference when it comes to Ukraine. However this does not mean that Russia has abandoned its former stance and become an expansionist power set on challenging the broader status quo.

First, although undoubtedly carried out using aggressive means, Russia’s intervention in Ukraine was actually defensively motivated. The February 2014 revolution in Kiev brought to power a radically pro-Western government that explicitly sought to reorient Ukraine away from Russia’s sphere of influence. This was perceived by Moscow to be an unacceptable threat to national security, especially because it was believed it would eventually lead to Ukrainian NATO membership. Were this to have occurred, the Alliance would have gained the strategically important Crimean peninsula, as well as a 1,200-mile frontier with Russia’s European heartland. To eliminate this danger, Russia permanently seized Crimea and is using the separatist movements in Donetsk and Lugansk to prevent Ukraine’s successful integration with the West.

Given that Russia’s actions are driven by a desperation to avoid strategic losses, and not a desire to make territorial gains, they are unlikely to be widely repeated, even if it is ultimately successful in Ukraine. The Baltic States and the former Warsaw Pact countries of Central Europe have already become part of the Western Alliance and this has been accepted by Moscow as an undesirable but unchangeable fact. The only case in which further aggression could therefore be expected is if another state deemed to be strategically important to Russia and located within its “near abroad” were also to seek to reorient itself towards the West. Were this, for example, to occur in Belarus, it is certain that Moscow would take steps to intervene. Overall then, it must be anticipated that Russia will remain ready to use military force to reverse strategic losses that are perceived to undermine core national security. Absent such threats, however, Russia can be expected to remain a supporter rather than a challenger to the international status quo.

China: A Revisionist Power That Needs Russia

While Russia is not a revisionist power, China unquestionably is. This is not a reflection of anything specific to China’s political system. Rather, it is simply the fact that, as with all rising powers before it, China’s international ambitions are growing in proportion to its economic and military might. Beijing is therefore seeking to make use of its greater clout to expand control over surrounding areas and to remake the international order to reflect its interests. This revisionist agenda is particularly pronounced in East Asia where China judges the status quo to be against it. This is above all due to the heavy presence of U.S. troops in Japan, South Korea, and Guam, as well as America’s regional naval dominance. China’s strategic goal is therefore to push the US out beyond the “first island chain” and thereby to establish its own hegemony within the East and South China Seas. Having achieved this, China will then look to extend its influence further into the Western Pacific. Undoubtedly at some point in this process Beijing will also seek to reintegrate Taiwan.

It would be nice to think that the expansion of China’s international ambitions could be managed peacefully. History, however, teaches that rising states tend to clash with established powers. The likelihood is therefore that the forthcoming decades will be an era of profound tension between China and the United States. These are commonplace observations. What is less often noted, however, is the pivotal role that will fall to Russia within this context of Sino-U.S. confrontation.

It may seem surprising given Russia’s faded international standing, but maintaining good relations with Moscow is a matter of great significance to Beijing. To begin with, this is because, in comparison with the United States, China has few close allies. This is especially true in the Asian region where China has territorial disputes with Japan, Vietnam, the Philippines, and India. Having friendly ties with at least one neighbor is therefore particularly important, especially since Russia can provide China with diplomatic support in key international institutions.

Even more fundamental is Russia’s strategic significance. By maintaining amicable relations with Russia, China is able to protect its otherwise exposed northern flank. From the 1960s to the 1980s, tense relations across this 2200-mile land border, helped ensure that much of China’s military potential had to remain focused in the northeast. It was only with the improvement in bilateral ties after 1989 and later settling of the countries’ border dispute in 2004 that China was able to concentrate fully on expanding its influence to the south and east. An instructive parallel in this regard is the way in which stable relations with Canada and Mexico have served as the foundation of U.S. international strength, providing Washington with a level of domestic security that has enabled it to focus on projecting power overseas.

Added to this is Russia’s importance as a resource exporter. At present, around 80 percent of China’s energy is imported from the Middle East and West Africa. This represents a major strategic vulnerability since, in the event of conflict, the United States would use its naval superiority to control the Malacca Straits and cut off the supply of these vital resources. Closer ties with Moscow help reduce this problem since Russia, along with Central Asian states, can provide oil and gas supplies via more easily protected overland pipelines.

Driving Russia And China Together

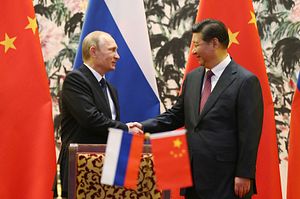

Evidently wise to these considerations, Beijing has been careful to cultivate closer ties with Moscow and Chinese leaders now routinely make Russia the destination of their first overseas visit. Beijing’s attentions in this regard have been generally welcomed in Russia yet, until recently, there had remained reluctance about embracing China fully.

Part of the hesitance is explained by Russian discomfort at the rapid reversal of the countries’ relative positions. It is not uncommon, for instance, to hear it remarked in Moscow that, having once been China’s older brother, Russia now finds itself in the role of younger sister. This loss of pride is also accompanied by economic concerns. Above all, there is the worry that in exporting little more than raw materials to China, Russia is increasingly tying itself into a semi-colonial relationship. When it comes to international politics too, many Russian are anxious that Moscow’s longstanding influence over Central Asia is being eclipsed by that of Beijing. Others fear an eventual Chinese takeover of the Russian Far East. This would come either via uncontrolled migration into the sparsely populated area or by direct annexation of territories that were historically Chinese until the second half of the 19th century.

The implications of this situation for U.S. policy are clear. If Washington wishes to contain China and ensure that it does not succeed in achieving regional hegemony in East Asia, it must finds ways of exploiting Russian fears and of driving a wedge between Moscow and Beijing. This would have the effect of depriving China of its solid rear and, with every increase in uncertainty along the Russian-Chinese border, Chinese maritime ambitions would be scaled back. Such thinking will be criticized by many as a relic of a previous era. However, as noted by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan, East Asia is now in a “similar situation” to that of Europe prior to the First World War. This being so, if a rising China is to be stopped from challenging the international status quo, it may be time for a revival of some old-fashioned realpolitik.

Blind to this logic, Washington’s current policy is working directly against long-term U.S. strategic interests. By imposing sanctions on Russia and threating to arm Ukraine, the United States has inadvertently succeeded in getting Russian policymakers to abandon their lingering anxieties and to rush headlong into China’s supportive embrace. Just as damagingly, Washington has lent heavily on allies to follow its policy prescription. Most notably, Japan, having recognized the disastrous implications of a China-Russia alliance for its own interests, had been pursuing a rapprochement with Moscow and was beginning to develop security ties, clearly with a view to drawing Russia away from China. This sensible approach has had to be suspended, however, as Washington pressured Tokyo into joining the sanctions effort.

The effects of U.S. policy have been all too apparent as Russian-Chinese cooperation has accelerated rapidly since March 2014. With regard to overall political relations, during his state visit to Shanghai in May, Putin gushed that bilateral interactions had become the “best in all their many centuries of history.” Striking also was the Russian president’s frequent use of the term “alliance,” albeit not with reference to military ties. In addition to this positive rhetoric, it was during the May trip that Russia and China finally signed their mammoth 30-year, $400 billion gas deal. After more than ten years of inconclusive negotiations, it seems that Western sanctions helped break the impasse by pushing Russia to accept China’s price terms.

In the arms sector too, Russia has shown a new willingness to make concessions. Having previously denied China access to its most advanced weaponry due to concerns over theft of intellectual property, Russia has now agreed to sell Beijing the S-400 air-defense system and Su-35 fighter. These technologies will help China extend its defensive coverage and strike range, thereby strengthening its position with regard to Taiwan and the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute. Further to weapons sales, bilateral naval cooperation has progressed and, following joint exercises in the East China Sea in May 2014, Russia and China agreed to conduct military drills in 2015 in the Mediterranean and Pacific. Last of all, sanctions have had a clear impact on Russian public opinion with attitudes towards China rapidly improving as those towards the West have soured. Indeed, according to an opinion survey conducted by the Levada Center in January 2015, a full 81 percent of Russians now regard the United States negatively whilst 80 percent have positive views of China. Each figure is the highest recorded in the history of the survey.

With the sanctions having gifted China so many benefits, Beijing must be privately cheering on Washington’s Russia policy.

What Is To Be Done?

Unless ways are found to draw Russia away from China again, this alignment is likely to solidify. To prevent this from happening, Washington rapidly needs to alter its stance.

First, there needs to be a change in mindset. Rather than considering Europe and Asia in isolation, as currently seems to be the case, U.S. decision makers need to recognize how their policies towards one region are connected to outcomes in the other. Additionally, there needs to be a shift in the way Russia is seen. At present, many in Washington persist in the Cold War view that Russia is an expansionist power which, given half a chance, would send its tanks rolling on European capitals. Such fears wildly exaggerate Russia’s capabilities and demonstrate a failure to understand the transformation of Russia’s status from a global to a regional power. Moscow’s strategic priority is to aggressively defend its current standing in international politics against what it sees as persistent Western attacks. It does not have ambitions to uproot the global system. This being so, attempting to oppose Russian expansionism is a damaging distraction. If the U.S. is to maintain primacy in the 21st century, it must instead recognize that China is its primary geostrategic rival and subordinate other foreign policy goals to the paramount objective of containing its rise.

None of this is to say that Washington should take no role in the resolution of the Ukraine crisis. Quite the reverse, it is essential that the U.S. help bring the war to a rapid conclusion. Once this has been achieved, relations between Russia and the West can be gradually detoxified and long-term efforts can begin to encourage Moscow to distance itself from Beijing.

The key to ending the conflict is to permanently exclude the possibility of Ukraine’s membership of NATO. It was the Alliance’s reckless decision in April 2008 to declare that both Ukraine and Georgia “will become members” that intensified Russian insecurity, provoking its aggressive response to defend the status quo. It might be a different matter if Ukraine could be successfully integrated into the Western bloc, but this is unrealistic. While Western governments are half-hearted about this possibility, Russia is absolutely determined in its opposition. Since the reorientation of Ukraine towards the West is seen as a fundamental security threat, Moscow will be willing to bear considerable costs to prevent this from happening. Sanctions will therefore have no effect. Arms supplies to the Ukrainian government, meanwhile, will only make things worse by aggravating Russian insecurity and forcing Moscow into further escalation that the West would be reluctant to match.

As distasteful as it may be to give in to Russia’s demands, in the interests of lasting peace Western governments should reassure Moscow that Ukraine will not be admitted to NATO. Unfortunately, since Moscow believes that NATO broke an earlier promise not to expand eastward following the end of the Cold War, a verbal commitment will not be sufficient. Instead, an additional guarantee is required. This can be provided via the creation of a federal structure for post-conflict Ukraine that gives regions veto rights over fundamental foreign policy and security decisions, such as membership of military alliances. As well as satisfying Ukrainian rebels and their Russian backers with regard to NATO, this mechanism would have the benefit of ensuring that Ukraine could never be dragged into any Russian-dominated organization against the will of its Western regions.

With Ukraine thus established as a neutral country, Russia will become a more reasonable neighbor. Its fears assuaged, Moscow will reduce its support for the rebels, permit the closure of the border, and allow the reintegration of the breakaway areas of Donetsk and Lugansk. Since Russia is a status quo power, these concessions will not encourage further aggression. Despite this, to reassure NATO members in Eastern Europe, the Alliance should establish permanent military bases in Poland, reaffirm the commitment to defend the Baltic States, and persuade members to honor their pledge to increase defense spending to 2 percent of GDP. These measures will not please Moscow, but improvements in the security of existing NATO members are not perceived as comparable to the threat posed by expansion of the Alliance into Russia’s nearest “near abroad.”

Having reestablished security in Europe, the United States can return its attention to the priority of containing China. An important part of this will involve selective courting of Russia (such as by offering membership of the Trans-Pacific Partnership) and rekindling the frictions between Moscow and Beijing that have been extinguished in recent months.

Overall, it must be said that this is a highly disagreeable outcome for Ukraine that shatters many of its people’s dreams of Western integration. The alternative, however, is an approach that will only serve to prolong bloody conflict while actively encouraging the formation of a powerful Chinese-Russian axis that will present a formidable challenge to U.S. interests in the Asia-Pacific and beyond for decades to come. If this is the result of Washington’s Ukraine policy, it will surely come to be seen as one of the greatest geopolitical mistakes of the 21st century.

James D.J. Brown is Assistant Professor in Political Science at Temple University, Japan Campus. His main areas of expertise are Russian-Japanese relations and international energy politics. His research has previously been published in the journals of International Politics, Politics, Asia Policy, and Post-Soviet Affairs. He is also a frequent media contributor on issues related to international relations in North-East Asia.